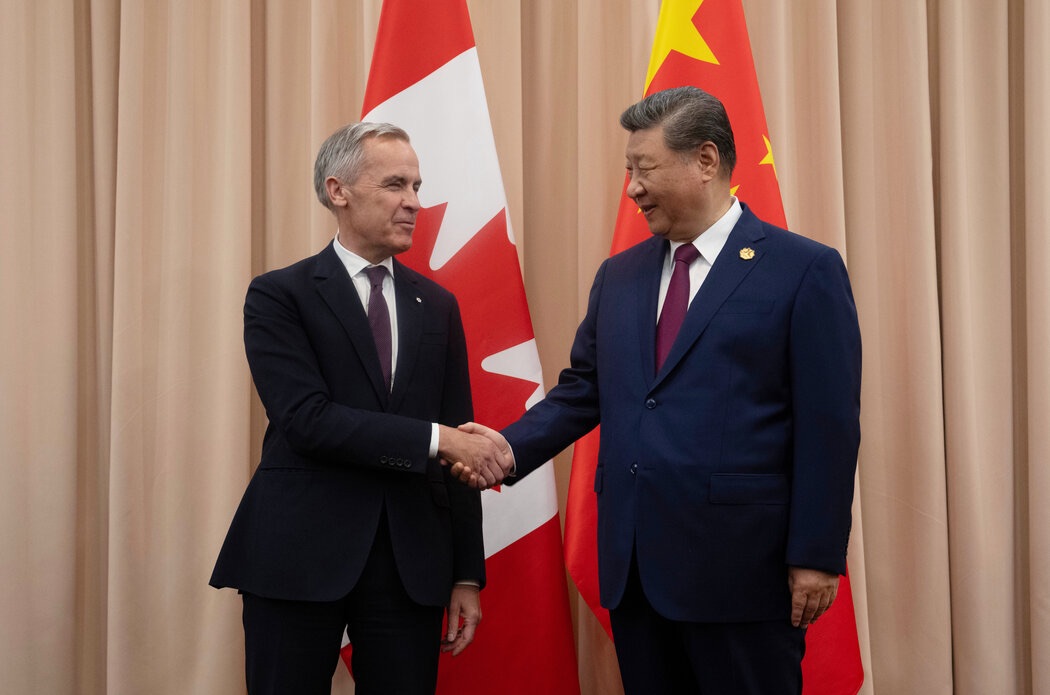

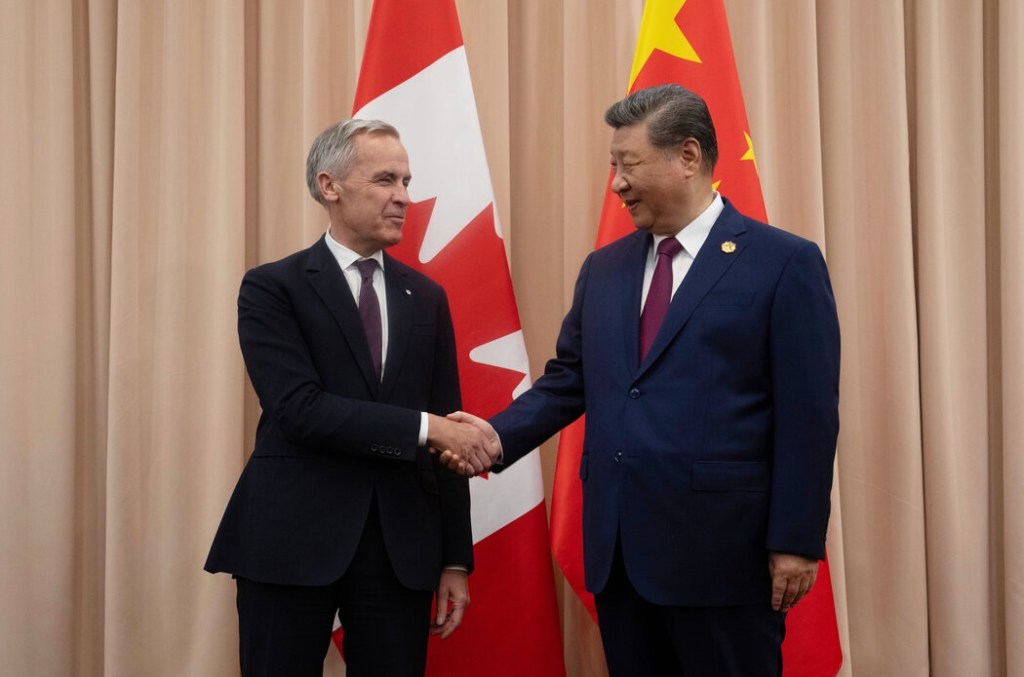

On January 15, 2026, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney visited China and met with Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Premier Li Qiang, among others. The two sides signed a joint statement and a number of economic and trade cooperation agreements. This marked the first visit to China by a Canadian prime minister in eight years and signified a comprehensive warming of China–Canada relations.

In 2018, the arrest in Canada of Huawei Vice President Meng Wanzhou, as well as China’s subsequent detention of two Canadian citizens as “hostages,” led to a sharp cooling of China–Canada relations. By the time of the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Canada in 2020, both sides were very restrained and did not hold any warm celebrations.

In the years that followed, Canada also participated in a series of Western measures against China, including “decoupling,” trade confrontations, and sanctions triggered by human rights issues. China likewise imposed a number of retaliatory sanctions on the Canadian side.

So why, by 2026, did the Canadian prime minister decide to visit China, and why did the Chinese side receive him warmly, successfully signing many important cooperation agreements and issuing a joint statement?

The specific reasons are very complex, but in brief, they lie in the tremendous changes in the international situation facing both countries. Among these, the dramatic shift in Canada’s relationship with the United States in particular played a key role in bringing about the change in Canada’s position.

For a long time, the United States and Canada have been very friendly, highly trusting allies. Although historically the United States and Canada, then under British rule, briefly went to war, over the subsequent two centuries the two sides have remained at peace, with very close economic, trade, and people-to-people exchanges, and an almost undefended border. In international wars such as World War I, World War II, and the Korean War, Canada stood on the same side as the United States. Canada also supported U.S. military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The United States and Canada are both members of the “Five Eyes” alliance, dominated by populations of Anglo-Saxon origin, and their relationship is even closer than that with Western countries outside the alliance. During the period from 2021 to 2024, when Joe Biden served as President of the United States, the two countries maintained close cooperation and, together with the broader Western camp, jointly promoted a strategy of “decoupling” from China.

However, after Donald Trump was elected president of the United States for a second time, he openly put forward territorial claims such as “Canada should become a state of the United States,” showing a lack of respect for Canadian sovereignty and dignity, and launched a trade war against Canada. The U.S. government, dominated by right-wing populist forces represented by Trump and Vance, initiated attacks across multiple fields, including trade, ideology, and the distribution of interests, against the Western political establishment, including Canada.

This greatly worsened U.S.–Canada relations and created major rifts within what had previously been a relatively united Western camp. Faced with the aggressive pressure of a powerful and overbearing neighbor to the south, Canada, in order to protect itself and push back, gradually abandoned its earlier approach of joining other Western countries in sanctioning China—a country with a fundamentally different system and sharply contrasting values that poses a major challenge to the Western-led order—and instead moved toward easing relations.

For Canada, the earlier conflicts with China, especially the hostage incident, were indeed painful, and institutional differences also made it difficult for Canada to trust China. But in the face of new changes in the international situation, a rupture with the United States, the growing “law of the jungle” in the world order, and Canada’s own domestic economic and social difficulties, choosing to cooperate with a country as economically massive as China became a path that was taken reluctantly but out of necessity.

Not only Canada, but also many Western countries that in previous years enthusiastically participated in “decoupling” from China and in military, technological, and economic efforts to guard against and contain China, have undergone similar shifts.

France, for example, which has long been relatively independent within the Western camp and unwilling to follow the United States unquestioningly, saw President Macron visit China late last year for cordial exchanges with the Chinese side. Human rights issues were set aside, trade disputes were downplayed, and economic and cultural cooperation was strengthened.

The United Kingdom, after a period of strained relations with China over Hong Kong several years ago, has also gradually deemphasized the Hong Kong issue, turned to strengthening ties with China, and is preparing to approve the construction of a Chinese “super embassy” in the UK. Germany, Australia, Italy, and other countries have likewise adopted a pragmatic approach toward cooperation with China and no longer emphasize the issue of “decoupling.”

The shift in the attitudes of these countries shares many similarities with Canada’s. They have all felt the strong isolationist and hegemonic behavior of the United States since Trump and right-wing populist forces came to power, including trade wars, a tilt toward Russia and away from Ukraine, and attacks on the ruling establishments of various countries, along with the direct, practical troubles and dangers these policies have created. At the same time, each of these countries faces domestic challenges such as economic downturns, ethnic tensions, intensifying social conflicts, and the gradual disintegration of traditional political orders.

Under these circumstances, the alliance network that once, on the basis of shared interests and liberal democratic values, united to “decouple” from China and to contain countries such as China and Russia has clearly developed serious cracks. Although the alliances among Western countries have not completely collapsed, they can no longer maintain the same level of unity and coordination as before and are increasingly focused on their own national interests.

Once one country seeks cooperation with China and benefits from its massive volume of trade, the encirclement is broken, and other countries will no longer rigidly adhere to their principles. China has also deliberately taken advantage of this dynamic to divide the West, and it has indeed achieved results.

Moreover, after several years of “decoupling,” Western countries have discovered that it is now very difficult to truly disengage from China. China’s population and economic scale are enormous, and its productivity, labor force, and market are difficult to replace. India and Southeast Asian countries cannot fully substitute for China’s role in Western trade and economic relations.

Even if the West can reduce cooperation with China in a limited number of areas involving security and high-end technology, it is, overall, very difficult to achieve a complete “decoupling and severing of supply chains” from China. Under globalization, the West and China are mutually dependent and hard to separate.

As a result, in the past two years, countries such as France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada, as well as the European Union, have become less insistent on a hardline approach toward China and have instead tended toward easing relations. The once-prominent “decoupling” and strategic containment have thus been set aside and cooled.

However, the easing of relations between Western countries and China does not mean that the two sides have truly established reliable and trusting relationships or that the future is bright. Because of differences in systems and ideology, competition in trade and the economy, human rights issues, and the Taiwan question, there are deep-rooted contradictions and difficult-to-bridge divides between the two sides.

Under the current circumstances, the West and China are drawing closer to each other in order to make use of one another and obtain what they need, rather than out of genuine affinity or sincere, close cooperation. Moreover, cooperation between China and the West is almost entirely concentrated in trade and a limited amount of cultural exchange. Even if relations warm further, breakthroughs in the political, military, and international strategic spheres are unlikely, and both sides will remain standing before a deep and unfathomable divide.

The West’s pause in “decoupling” from China in areas such as trade does not mean that it will never “decouple” again. If the United States once again comes under the control of the political establishment, if Western countries regain strength, or if relations between China and the West deteriorate over certain issues, “decoupling” could be restarted.

Conversely, if China in the future becomes even stronger and more confident and no longer seeks the West, it may likewise shift from its current relatively friendly posture to a harder line, becoming more dismissive of Western human rights criticisms and critiques of its development model, and treating the West with greater indifference and severity.

For decades, relations between the Western camp and China have gone through repeated ups and downs, and individual countries have each experienced their own periods of warmth and cooling in their ties with China. Changes in the domestic politics of China and Western countries (including within the European Union) and shifts in the international situation all affect the quality of their relations.

It is not surprising that China–Canada relations are warming today and China–Europe relations are easing, only to potentially deteriorate again in a few years. All parties should be prepared for this. It is neither appropriate to be pessimistic and constantly predict the collapse of China–West relations, nor to be overly optimistic.