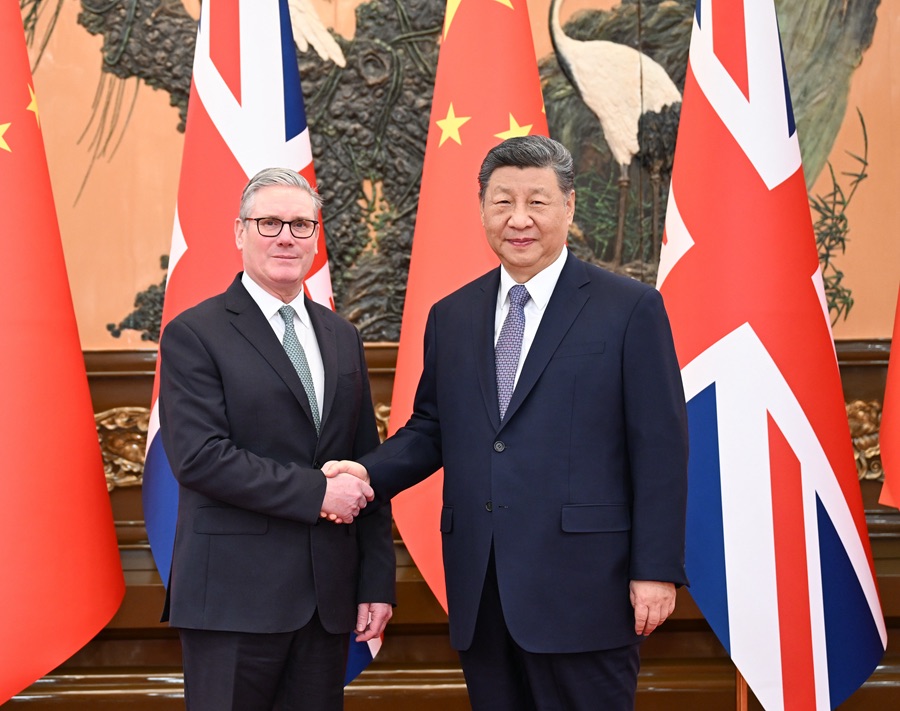

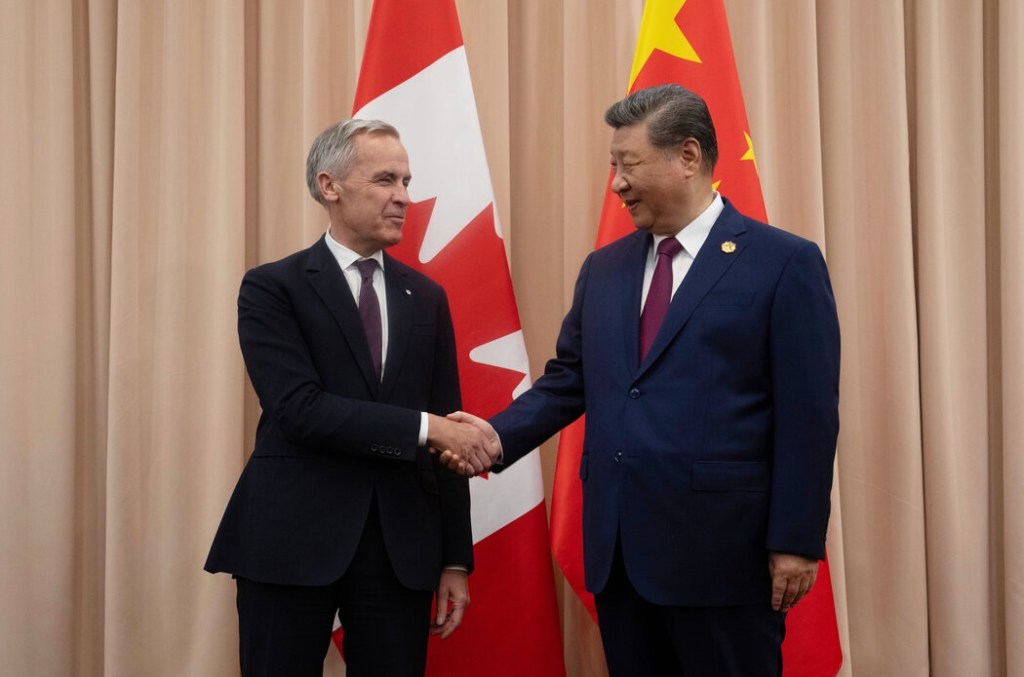

On January 28, 2026, British Prime Minister Keir Rodney Starmer visited China. This was the first visit by a British prime minister to China since 2018, marking a major turning point in the long-cooled UK–China relationship. Just days earlier, on January 20, the British government finally gave conditional approval to the long-delayed plan for China to build a “super embassy” in the United Kingdom.

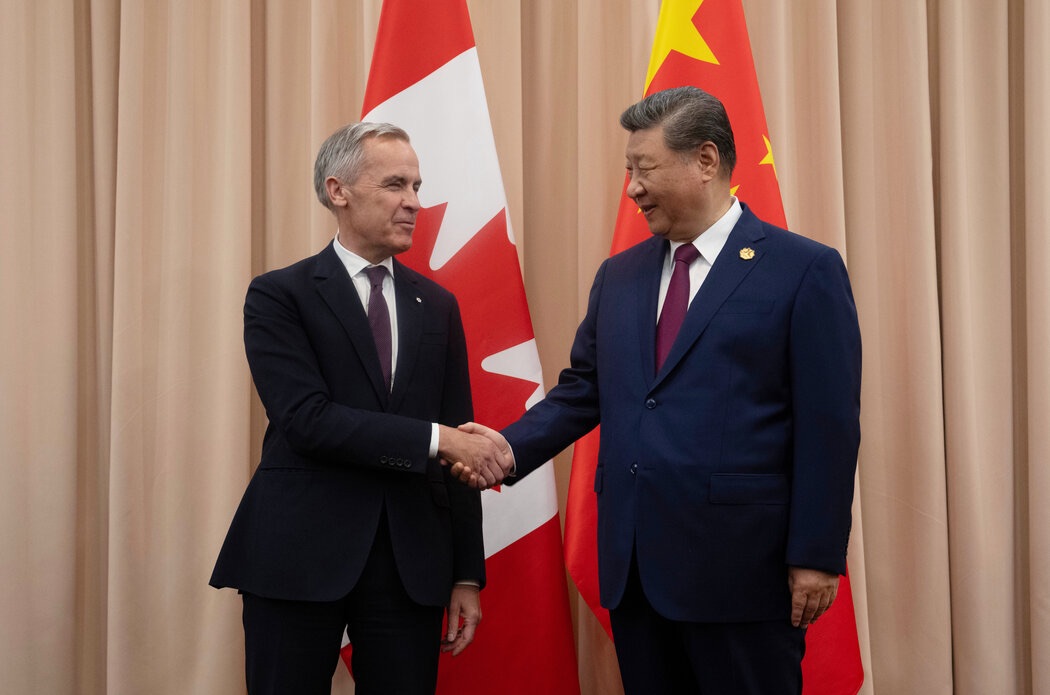

In December 2025, French President Emmanuel Macron visited China. On January 5 of this year, Irish Prime Minister Micheál Martin visited China. On January 25, Finnish Prime Minister Petteri Orpo visited China. In February, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz is also scheduled to visit China. The intensive visits by leaders of several major European countries reflect a gradual warming of Europe–China relations after years of chill.

Why did UK–China relations and Europe–China relations remain frozen for so long, why have they warmed recently, and where will they head in the future?

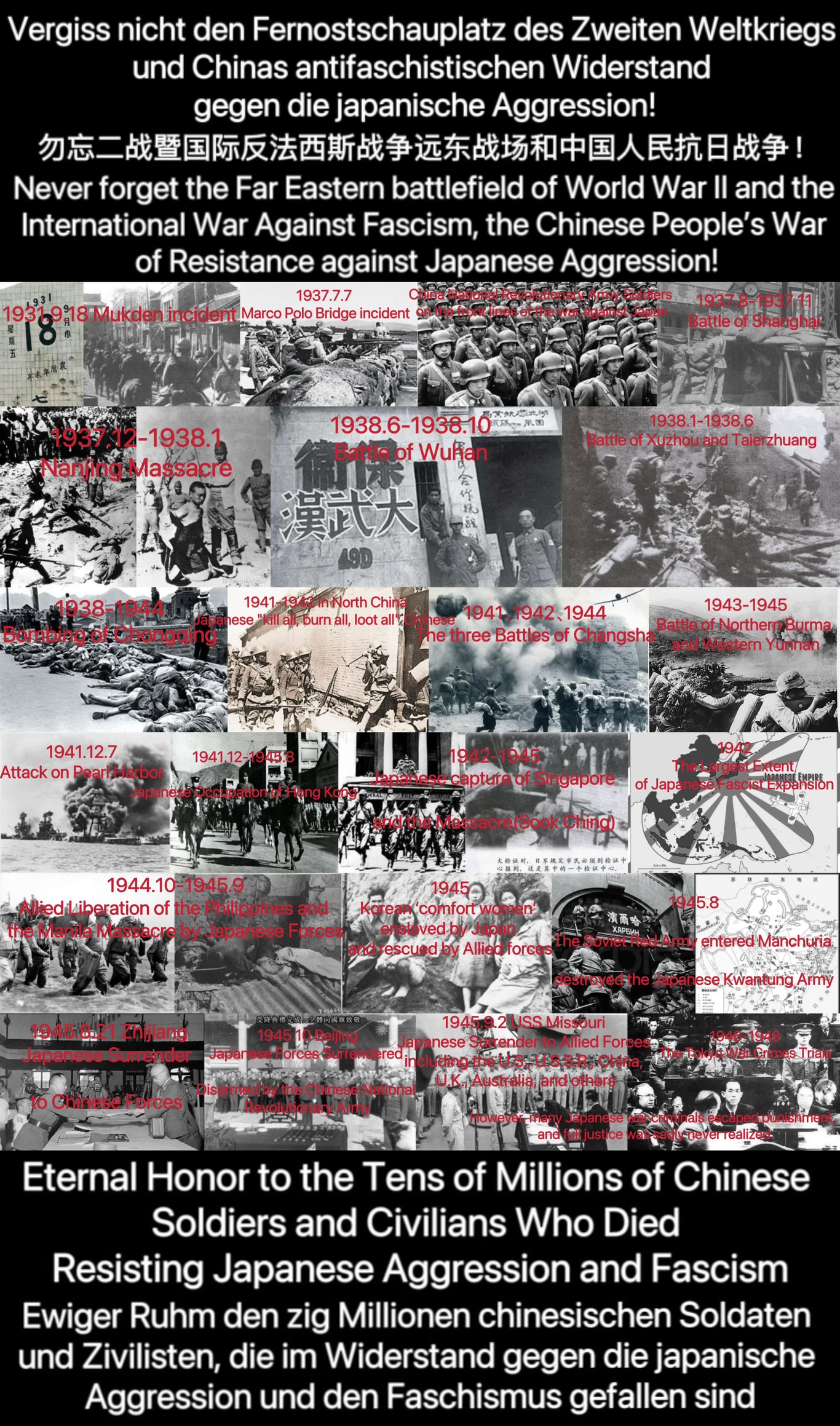

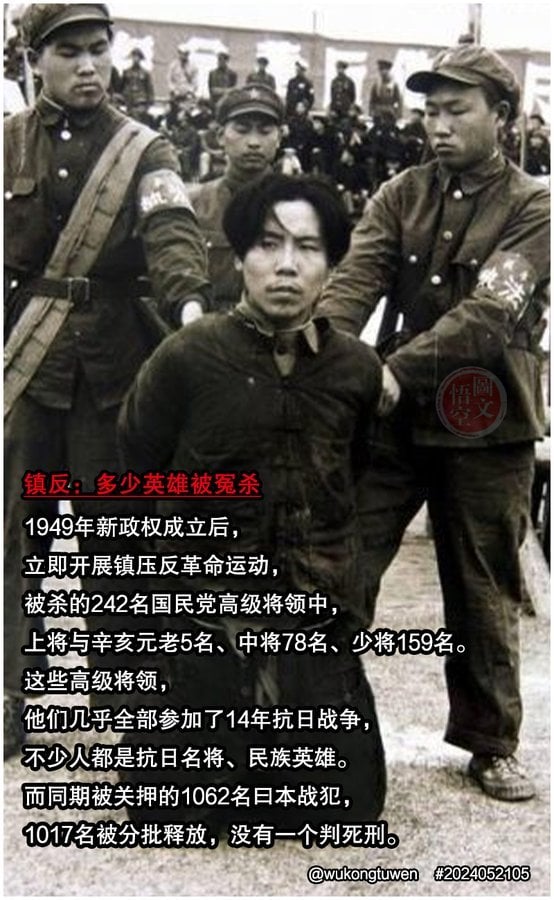

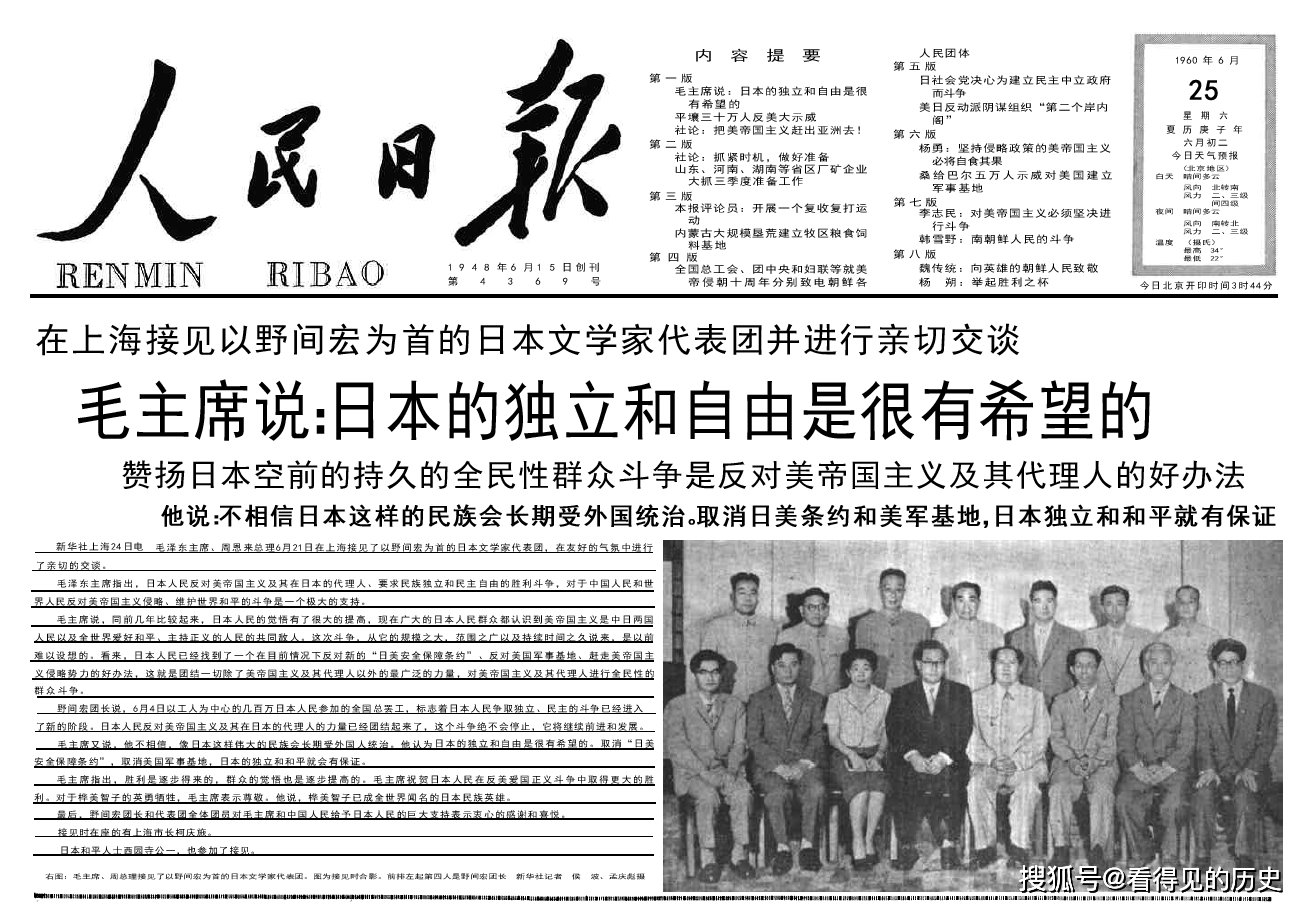

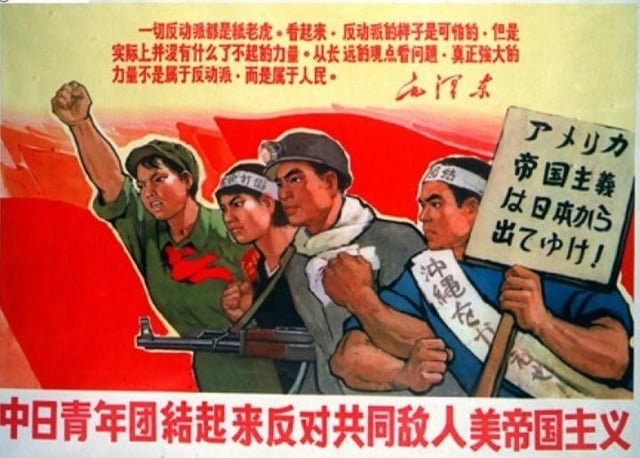

Historically, relations between the People’s Republic of China and European countries have gone through many ups and downs. The Cold War, the Korean War of 1950, and ideological confrontation once placed mainland China in long-term opposition to Western European powers such as the United Kingdom, France, and the Federal Republic of Germany.

It was not until the 1970s, when both China and Western Europe fell out with the Soviet Union and had mutual political and economic needs, that Western European countries and China established diplomatic relations and normalized ties. At that time, China’s relations with the Eastern European socialist states were relatively friendly. However, when China and the Soviet Union fell out, some of the pro-Soviet countries also became estranged from China for a period.

For several decades after the reform and opening-up, China maintained close economic and trade exchanges and extensive cooperation in many non-political fields with most European countries, including the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. As China’s economy developed, the volume of bilateral trade between China and Europe continued to increase, and China’s importance to European countries steadily rose. However, due to differences in political systems, China and Europe—especially China and countries such as the UK, France, and Germany—have never been able to achieve deep mutual trust or a higher level of cooperation.

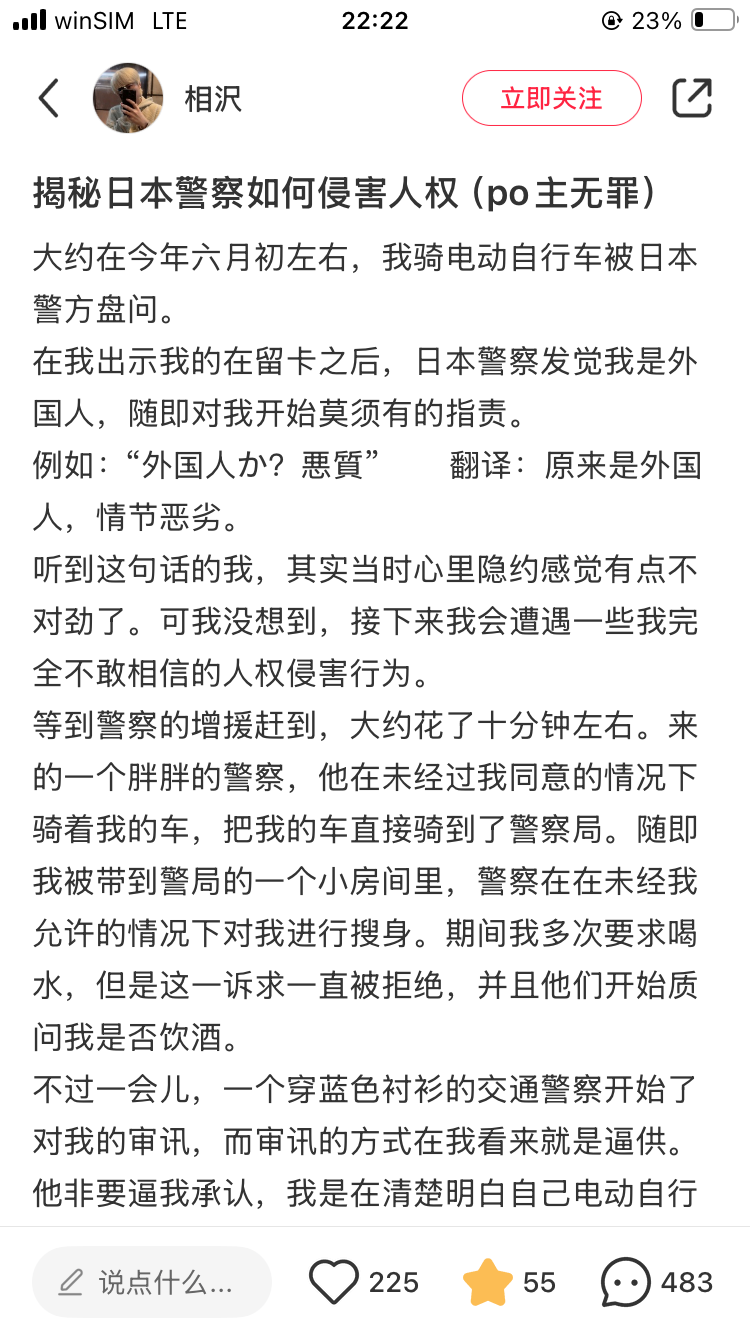

From the late 2010s to 2023, Europe–China relations deteriorated significantly, for a variety of reasons. Politically, China’s stalled political reforms, the intensification of authoritarianism, the detention of ethnic minorities in “re-education camps” in Xinjiang, the suppression of the Hong Kong anti-extradition movement, and other human rights issues led the European Union and European countries, which place great emphasis on human rights, to express strong dissatisfaction and impose sanctions. Public opinion and civil society attitudes toward China also worsened. China, in turn, adopted a number of countermeasures against the EU and countries such as the UK, France, and Germany.

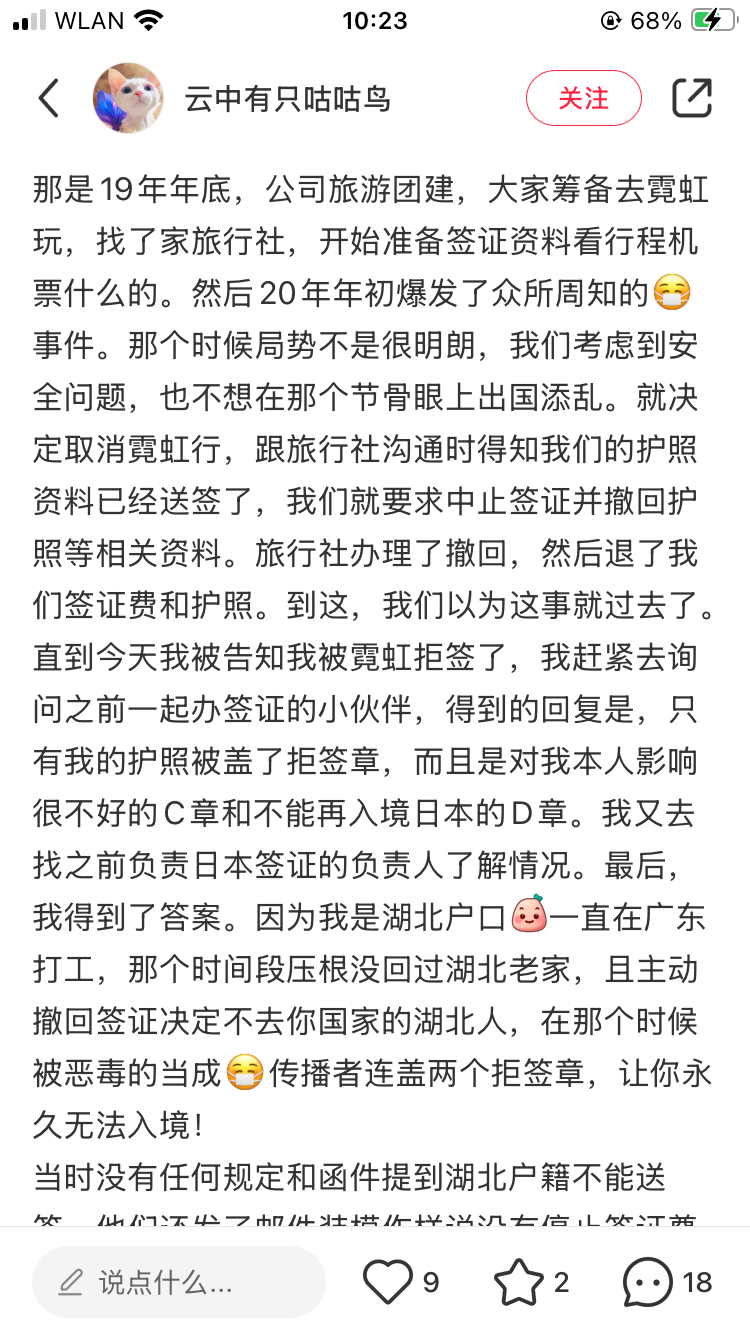

The COVID-19 pandemic, which originated in China from 2020 to 2022 and spread globally, as well as China’s “zero-COVID policy,” also hindered cooperation and exchanges between China and Europe. Differences in pandemic response models and a series of negative effects of China’s “zero-COVID” policy intensified model competition and confrontation between China and the West. From political systems to social governance models, China came under greater scrutiny across European circles. Fewer people praised Chinese culture, government governance capacity, or the perceived superiority of the “China model,” while negative perceptions and criticism increased further, and the former “China fever” receded.

Economically, Europe and China moved from a long period of division of labor and cooperation—Europe providing technology, China providing labor, sharing upstream and downstream roles in the industrial chain, and benefiting mutually—to a situation in which, as China’s economic and technological strength rose, it began to comprehensively challenge Europe. The relationship shifted from being primarily complementary to becoming increasingly competitive.

Moreover, China’s use of methods such as suppressing labor costs, providing state subsidies, and stealing commercial secrets to gain competitive advantages in less legitimate ways, along with allegations of dumping, also triggered European dissatisfaction and countermeasures, leading to constant trade frictions between China and Europe.

In geopolitics and international relations, the EU and countries such as the UK, France, and Germany formed a “values alliance” based on the foreign policy of liberal democratic “values” together with the United States, Canada, Australia, Japan, South Korea, and others, seeking to contain China. After the outbreak of the Russia–Ukraine war, China tilted toward Russia, which the EU perceived as an even greater threat, prompting responses toward both China and Russia and further intensifying the confrontation between China and Europe based on geopolitics and ideology.

Among the major European powers, the United Kingdom has been the most distant from China and has traditionally had relatively poorer relations with it. British foreign policy has long closely followed the United States, China’s largest competitor, and, due to the natural exclusionary tendencies of an island nation toward continental powers as well as conservative anti-communist ideology, UK–China relations have long been characterized as “hot economically, cold politically.”

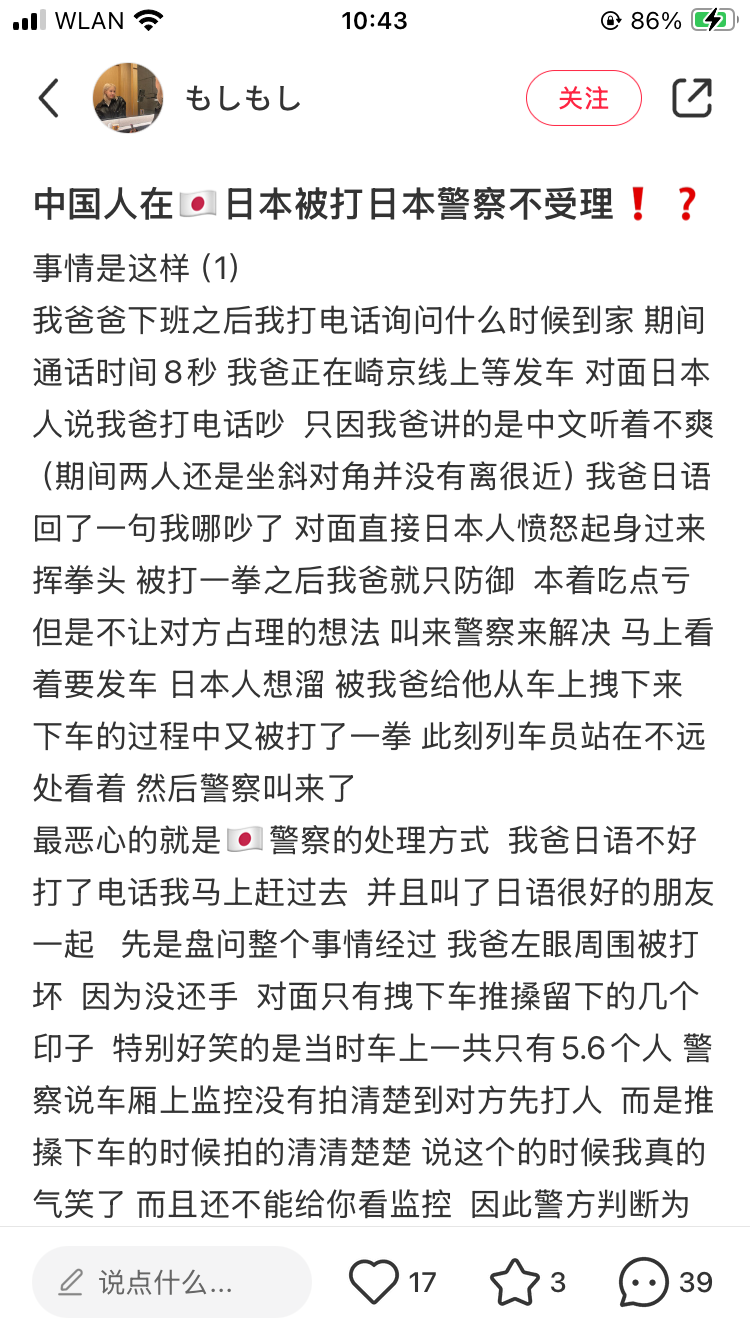

Following the 2019 Hong Kong anti-extradition movement and the subsequent crackdown, large numbers of Hong Kong residents fled to the United Kingdom. As the former colonial ruler of Hong Kong and the party that transferred Hong Kong’s sovereignty under the Sino-British Joint Declaration, the UK has been more involved in Hong Kong affairs and has reacted more strongly to Beijing’s actions there than other European countries.

The UK imposed sanctions on China and issued British National (Overseas) passports (BNO passports) to Hong Kong residents, granting them a status similar to British citizenship, providing refuge to many Hong Kong exiles opposed to the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese government, and allowing them to carry out long-term protest activities against China. China responded forcefully by imposing sanctions on a number of British officials and companies. This led to a marked deterioration in UK–China relations.

As a result of these multiple factors, around 2020, UK–China relations and Europe–China relations fell to their lowest point since the establishment of bilateral diplomatic ties. The UK and many European countries began to “decouple” from China, reducing cooperation and exchanges in areas such as trade, technology, and culture. If there had been no changes in the international situation, this state of affairs would likely have continued.

However, changes in the global situation over the past year—especially changes in relations between the United States and Europe—have profoundly altered the international landscape, prompting the UK and European countries to reconsider their relations with China and to shift their attitudes from cold to more moderate.

After Donald Trump formally took office as President of the United States in January 2025, he and the Republican governing team with strong right-wing populist tendencies carried out many “unorthodox” diplomatic actions. These included fiercely attacking traditional allies such as the UK, France, Germany, and the EU on ideological grounds; criticizing establishment domestic and foreign policies across countries; supporting populist forces within Europe in an attempt to overturn the existing system; launching tariff wars against European countries; drawing closer to Russia, which stands in opposition to Western Europe; distancing the United States from Ukraine, which the EU firmly supports; and repeatedly emphasizing that the United States no longer wishes to defend Europe and that Europe must assume responsibility for its own defense.

Vice President Vance’s speech at the Munich Security Conference in 2025, as well as the speeches by Trump and Musk at the 2026 Davos summit, all reflected the current U.S. administration’s disdain for the European establishment, its promotion of imperial hegemony, and its encouragement of populist politics.

Trump and the right-wing populism that dominates today’s U.S. foreign policy represent a regime that blends isolationism, hegemonism, and white supremacy, standing in stark contrast to the majority of European countries and the EU, which are dominated by establishment forces that advocate diversity, international cooperation, and an emphasis on equality.

Recently, Trump publicly put forward territorial claims over Greenland, which is located in Europe and is an autonomous territory of Denmark. Toward European countries that oppose U.S. annexation, Trump has used tariffs and military means as threats.

Trump has also shown contempt for the liberal democratic values cherished by the EU, displaying clear authoritarian and autocratic tendencies. Trump’s arrest of Venezuelan President Maduro, the bombing of Iran, and threats to overthrow Cuba and Colombia have all antagonized the EU, which values international law and the stability of the international order, and European countries also worry that their own security and stability could face similar threats.

For decades after World War II, the United States was a steadfast ally of Western European countries, and U.S. defense commitments to Europe were crucial. During the Cold War, it was with the support of U.S. forces that Europe was able to counter the militarily powerful Soviet Union. In the post–Cold War era, the United States and Europe remained closely aligned, jointly confronting challenges from China and Russia, the threat of terrorism, and together maintaining the international order established after World War II and the Cold War.

Since Trump’s return to office, a series of “crazy” diplomatic actions have shattered the traditionally close U.S.–Europe alliance, making countries such as the UK, France, and Germany feel that the United States has become unreliable or even dangerous. At the same time, Russia’s military threats, the rise of emerging countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America challenging Europe’s advantages and hegemony, and Europe’s own internal economic and social problems have left European countries feeling surrounded by crises.

In such circumstances, European countries all need to find new paths forward. Looking across the world, China is the strongest power outside the United States, with an economic scale comparable to the combined total of Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, and France. Re-examining and easing relations with China, and strengthening cooperation with it once again, thus becomes an option that cannot be avoided.

Compared with a United States that is extending the grasp of its hegemonic ambitions toward Europe, and a Russia that is militarily attacking Ukraine, China—though authoritarian at home and brutally repressive—appears in its foreign policy to be relatively more rational, restrained, and pragmatic, making it a more accessible and workable partner for the EU and countries such as the UK, France, and Germany.

In addition, after the “decoupling” of the past several years and the difficulties encountered in that process, European countries have also discovered that, given the enormous scale of China’s economy and the close, interdependent nature of China–Europe economic and trade relations, true “decoupling” is very difficult and comes at a heavy cost. Maintaining cooperation, by contrast, can help revive Europe’s sluggish economy.

As for human rights issues, in a world that is once again becoming jungle-like, and in a context where even the United States is openly trampling on human rights both domestically and internationally, the EU no longer has either the will or the capacity to take an especially tough stance on China’s human rights record. The issues of Hong Kong and Xinjiang, two of China’s major flashpoints, have also been gradually downplayed over time.

For China as well, there is likewise a need to work with Europe to counter the United States, promote economic development, and enhance China’s international influence. China’s economic performance in recent years has been weak, and the previous Western containment has indeed caused losses, creating a desire to improve relations with Western countries.

Compared with the United States, its largest competitor and long-term adversary, and Japan, with which it has historical grievances and current conflicts, European countries have fewer direct clashes with China and greater space for cooperation. With both China and Europe willing to engage and cooperate, it is only natural that leaders of several major European countries have come to visit China and that bilateral relations have warmed.

However, this round of easing in Europe–China relations is also limited, and voices of caution and measures of vigilance toward China remain numerous. During this visit by British Prime Minister Starmer, his remarks not only stated that cooperation with China “serves (the UK’s) national interests,” but also emphasized that differences remain with China and raised sensitive issues such as Hong Kong and Uyghur human rights with the Chinese side.

Improvements in UK–China and Europe–China relations are mainly reflected in the economic and trade sphere. Diplomatically, the two sides have only reached partial consensus on opposing U.S. hegemony and supporting multilateralism, while in political and military terms they remain fundamentally in a state of opposition. Meanwhile, opposition parties such as the UK Conservative Party have criticized Starmer’s visit to China and his government’s approval of the construction of China’s “super embassy.”

Moreover, just two days before Starmer’s visit to China, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen made a high-profile visit to India, reaching major agreements with the Indian side, including the establishment of an EU–India free trade area. The French President Macron, who visited China at the end of last year, is also scheduled to visit India in February this year.

This reflects that Europe will not “put all its eggs in one basket” by becoming overly dependent on China, but will simultaneously court another populous developing power, India, as a partner and as a counterbalance to China. Compared with China, which has a very different political system, India, which shares a democratic system, is more trusted by Europe.

Europe is also strengthening its relations with Japan, South Korea, and countries in Southeast and South Asia, cooperating in many fields, likewise out of a need to balance China and diversify risks. For example, on January 29, European Council President António Costa visited Vietnam, coinciding with Starmer’s trip to China. Over the past year, European leaders and EU officials have also repeatedly visited Japan. These visits by European political figures to China’s neighboring countries are not only meant to consolidate bilateral ties, but undoubtedly also serve the purpose of constraining China.

There are also some countries, parties, and individuals in Europe whose stance toward China remains consistently very hardline, and who refuse to shift toward a more moderate approach in line with changing circumstances. For example, Eastern European countries such as Lithuania, for ideological and geopolitical reasons, have sharply criticized China, which maintains close relations with Russia, and have strongly supported Taiwan.

Some European political figures who focus on Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and China’s human rights issues—including EU and national officials, members of national parliaments, and Members of the European Parliament—also advocate a tough line on China and seek to prevent national governments and the EU from moving toward a more moderate China policy. These factors also form obstacles to the warming of Europe–China relations.

Therefore, the shift toward a more positive attitude toward China by countries such as the UK, France, and Germany, as well as by the EU, is limited in degree, and the estrangement between the two sides continues to exist. For instance, although the UK government has approved China’s “super embassy” project in the UK, it has attached conditions, reflecting the dual nature of the UK’s approach to China as both more positive and yet still reserved. Other European countries and the EU are similar: while cooperating with China under a pragmatic diplomatic approach, such cooperation is not “without limits” but rather subject to many constraints.

Europe’s easing toward China is clearly not entirely voluntary, but rather the result of the aforementioned “betrayal” by the United States and the worsening of internal problems within European countries, which have compelled Europe to ease relations with China in order to reduce international and domestic pressure.

The international situation and domestic politics in each country are constantly changing: former adversaries may become allies, and former partners may become enemies in the future, while national conditions and public opinion also rise and fall. China’s efforts to improve relations with Europe are likewise driven by practical needs. Lacking a shared foundation of values, the mistrust and wariness between the two sides will not disappear simply because relations have warmed.

If Trump and U.S. populist forces were to lose influence in the coming years, and the United States were to once again elect a new president and a congressional majority committed to allying with Europe to counter China and Russia, thereby re-forming and strengthening a “values alliance,” then Europe’s attitude toward China could shift once more. If internal problems within European countries were alleviated, or if hardline governments toward China were elected in most countries, then in areas of disagreement between China and Europe—such as trade, human rights, and the Taiwan issue—the stance of national governments and the EU toward China would become more forceful, and Europe–China relations could very well deteriorate again.

Personally, the author holds a generally positive view of improvements in Europe–China relations. The easing of Europe–China relations is beneficial to the development of bilateral trade, to improvements in domestic economies and livelihoods on both sides, to exchanges in science, technology, and culture, to mutual communication and understanding among peoples of different countries and ethnic groups, to regional stability, and to world peace. The author has consistently opposed “decoupling” and intense confrontation between the West and China, and instead advocates handling bilateral and multilateral relations in a more constructive manner and resolving disputes through compromise.

At the same time, the author also hopes that European countries will pay attention to human rights issues in China and, in various forms, promote the advancement of civil rights and improvements in people’s livelihoods in China. Moreover, while Europe has long paid attention to Hong Kong, Taiwan, Xinjiang, and Tibet, which has its reasons, it has neglected the human rights situation of the Han Chinese, who constitute the majority of Mainland China’s population and whose rights also deserve attention.

Europe, which ranks among the world’s leaders in material living standards and rights protections, should, through various means—including methods that carry less overt political coloration and are more acceptable to the Chinese side—promote the well-being of the Chinese people. This, too, would contribute to a more enduring and genuine friendship and peace between Europe and China.

This article is written by Wang Qingmin (王庆民), a Chinese writer based in Europe and a researcher in international politics.